A laser is sent down a UMD hallway in an experiment to corral light as it makes a 45-meter journey. Credit: Intense Laser-Matter Interactions Lab, UMD

It’s not at every university that laser pulses powerful enough to burn paper and skin are sent blazing down a hallway. But that’s what happened in UMD’s Energy Research Facility, an unremarkable looking building on the northeast corner of campus. If you visit the utilitarian white and gray hall now, it seems like any other university hall—as long as you don’t peak behind a cork board and spot the metal plate covering a hole in the wall.

But for a handful of nights in 2021, UMD Physics Professor Howard Milchberg and his colleagues transformed the hallway into a laboratory: The shiny surfaces of the doors and a water fountain were covered to avoid potentially blinding reflections; connecting hallways were blocked off with signs, caution tape, and special laser-absorbing black curtains; and scientific equipment and cables inhabited normally open walking space.

As members of the team went about their work, a snapping sound warned of the dangerously powerful path the laser blazed down the hall. Sometimes the beam’s journey ended at a white ceramic block, filling the air with louder pops and a metallic tang. Each night, a researcher sat alone at a computer in the adjacent lab with a walkie-talkie and performed requested adjustments to the laser.

Left to right: Eric Rosenthal, a physicist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory; Anthony Valenzuela, a physicist at the U.S. Army Research Lab; and Andrew Goffin, a UMD electrical and computer engineering graduate student, align optics at a porthole in the wall in order to send the laser beam from the lab down the hallway. Credit: Intense Laser-Matter Interactions Lab, UMD

Their efforts were to temporarily transfigure thin air into a fiber optic cable—or, more specifically, an air waveguide—that would guide light for tens of meters. Like one of the fiber optic internet cables that provide efficient highways for streams of optical data, an air waveguide prescribes a path for light. These air waveguides have many potential applications related to collecting or transmitting light, such as detecting light emitted by atmospheric pollution, long-range laser communication or even laser weaponry. With an air waveguide, there is no need to unspool solid cable and be concerned with the constraints of gravity; instead, the cable rapidly forms unsupported in the air. In a paper accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review X the team described how they set a record by guiding light in 45-meter-long air waveguides and explained the physics behind their method.

The researchers conducted their record-setting atmospheric alchemy at night to avoid inconveniencing (or zapping) colleagues or unsuspecting students during the workday. They had to get their safety procedures approved before they could repurpose the hallway.

“It was a really unique experience,” says Andrew Goffin, a UMD electrical and computer engineering graduate student who worked on the project and is a lead author on the resulting journal article. “There’s a lot of work that goes into shooting lasers outside the lab that you don’t have to deal with when you’re in the lab—like putting up curtains for eye safety. It was definitely tiring.”

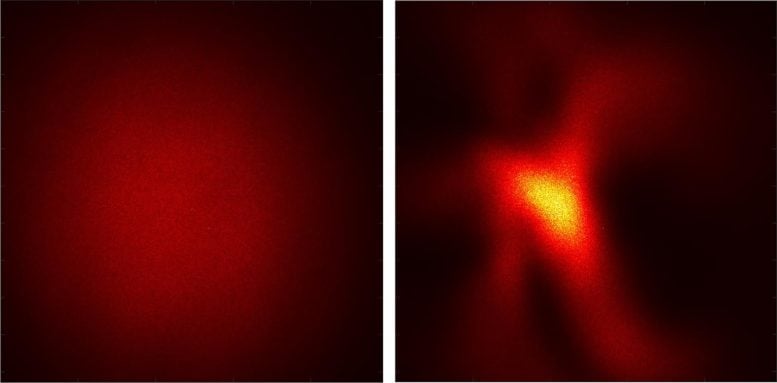

Distributions of the laser light collected after the hallway journey without a waveguide (left) and with a waveguide (right). Credit: Intense Laser-Matter Interactions Lab, UMD

All the work was to see to what lengths they could push the technique. Previously Milchberg’s lab demonstrated that a similar method worked for distances of less than a meter. But the researchers hit a roadblock in extending their experiments to tens of meters: Their lab is too small and moving the laser is impractical. Thus, a hole in the wall and a hallway becoming lab space.

“There were major challenges: the huge scale-up to 50 meters forced us to reconsider the fundamental physics of air waveguide generation, plus wanting to send a high-power laser down a 50-meter-long public hallway naturally triggers major safety issues,” Milchberg says. “Fortunately, we got excellent cooperation from both the physics and from the Maryland environmental safety office!”

Without fiber optic cables or waveguides, a light beam—whether from a laser or a flashlight—will continuously expand as it travels. If allowed to spread unchecked, a beam’s intensity can drop to un-useful levels. Whether you are trying to recreate a science fiction laser blaster or to detect pollutant levels in the atmosphere by pumping them full of energy with a laser and capturing the released light, it pays to ensure efficient, concentrated delivery of the light.

Milchberg’s potential solution to this challenge of keeping light confined is additional light—in the form of ultra-short laser pulses. This project built on previous work from 2014 in which his lab demonstrated that they could use such laser pulses to sculpt waveguides in the air.

The short pulse technique utilizes the ability of a laser to provide such a high intensity along a path, called a filament, that it creates a DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevX.13.011006