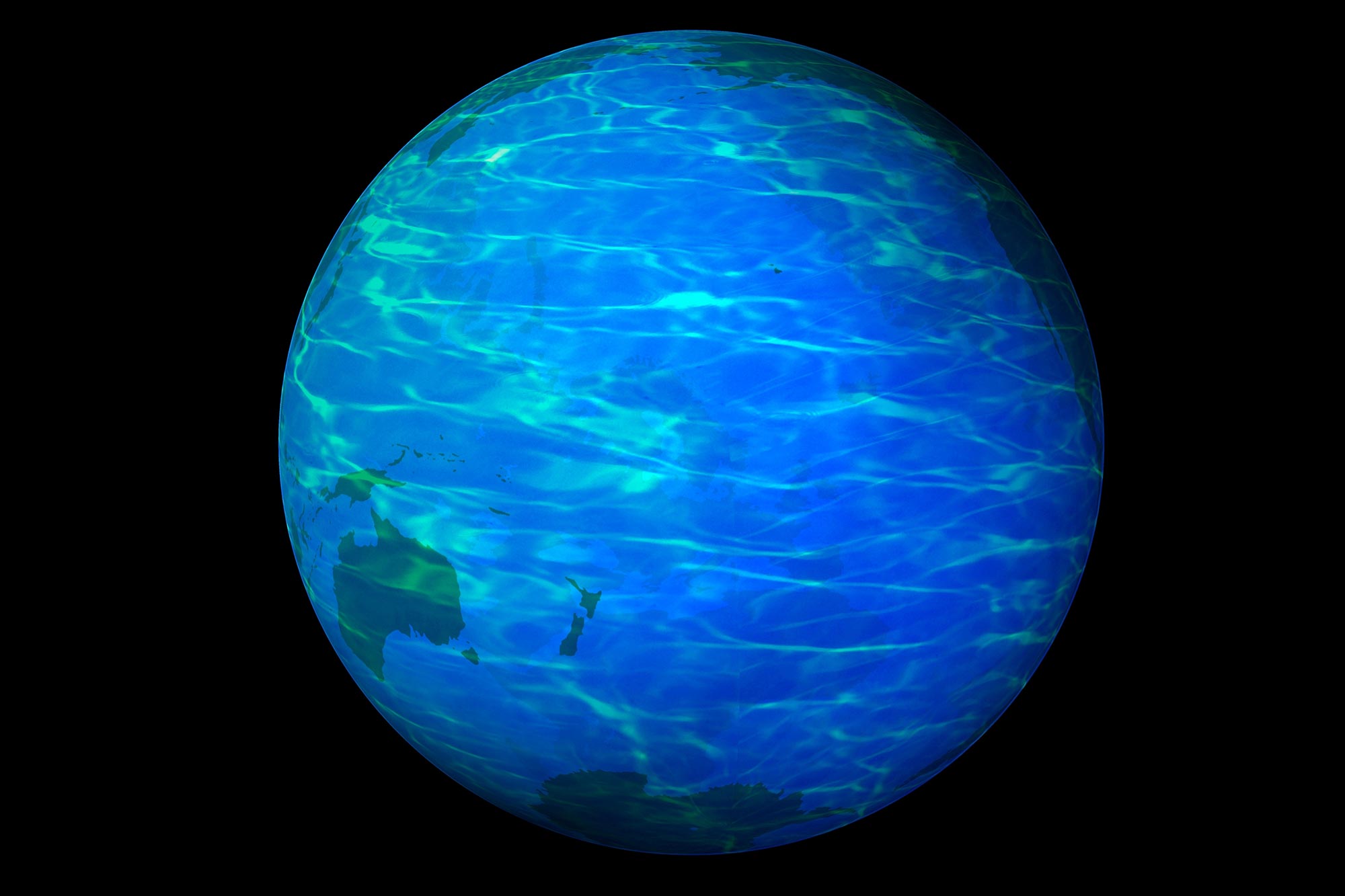

Many more planets may have large amounts of water than previously thought, according to new research. However, much of that water is likely embedded in rock, rather than in surface oceans as depicted in this illustration.

New analysis finds evidence for many exoplanets made of water and rock around small stars.

Water is the one thing all life on Earth requires. Additionally, the cycle of rain to river to ocean to rain is an essential part of what maintains our planet’s stable and hospitable climate conditions. Planets with water are always at the top of the list when scientists discuss where to search for signs of life throughout the galaxy.

Many more planets may have large amounts of water than previously thought—as much as half water and half rock, according to a new study. The catch? All that water is likely embedded in the rock, rather than flowing as oceans, lakes, or rivers on the surface.

“It was a surprise to see evidence for so many water worlds orbiting the most common type of star in the galaxy,” said Rafael Luque. He is first author on the new paper and a postdoctoral researcher at the more and more exoplanets—planets in distant solar systems. With a larger sample size, scientists are better able to identify demographic patterns. This is similar to how looking at the population of an entire town can reveal trends that are hard to see at an individual level.

Luque, along with co-author Enric Pallé of the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands and the University of La Laguna, decided to take a population-level look at a group of planets that are seen around a type of star called an M-dwarf. These stars are the smallest and coolest kind of star in the main sequence and the most common stars we see around us in the galaxy. Scientists have cataloged dozens of planets around them so far.

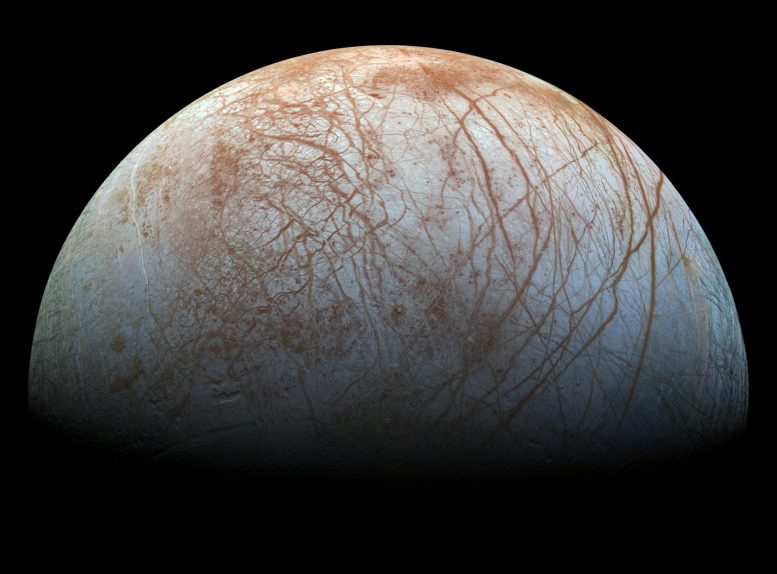

A new study suggests that many more planets in distant solar systems have large amounts of water than previously thought—as much as half water and half rock. The catch? It’s probably embedded underground, as in Jupiter’s moon Europa, above. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute

However, because stars are so much brighter than their planets, we cannot see the actual planets themselves directly. Instead, astronomers detect faint signs of the planets’ effects on their stars—the shadow created when a planet crosses in front of its star, or the tiny tug on a star’s motion as a planet orbits. This means that many questions remain about what these planets actually look like.

“The two different ways to discover planets each give you different information,” said Pallé. By catching the shadow created when a planet crosses in front of its star, astronomers can determine the diameter of the planet. By measuring the tiny gravitational pull that a planet exerts on a star, astronomers can calculate its mass.

Scientists can get a sense of the makeup of the planet by combining the two measurements. Perhaps it’s a big-but-airy planet made mostly out of gas like Jupiter’s moon Europa, which is thought to have liquid water underground.

“I was shocked when I saw this analysis—I and a lot of people in the field assumed these were all dry, rocky planets,” said UChicago James Webb Space Telescope, DOI: 10.1126/science.abl7164

The majority of the research was performed as Luque’s Ph.D. thesis at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands.

Funding: Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Centre of Excellence “Severo Ochoa” award to the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia, Spanish Ministry of Economics and Competitiveness, Spanish Ministry of Universities, Next Generation EU.