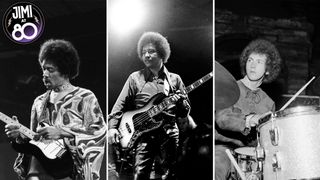

Jimi at 80: Born in Seattle on November 27, 1942, Jimi Hendrix would have celebrated his 80th birthday this week. Throughout this week on Guitar World, we’ll celebrate his genius and game-changing impact on the world of guitar playing.

This interview with Hendrix’s former rhythm section – drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Billy Cox – was first published in the October 2005 issue of Guitar World.

It is a typically beautiful early summer day in downtown Nashville, Tennessee. As I sit in the exquisite lobby of the five-star Hermitage Hotel, beneath the intricately detailed and expansive stained glass ceiling, the 97-degree weather has given way to a torrential downpour, the likes of which have not been seen since the Great Flood.

Seated on the Louis XIV–style couch in front of me are Mitch Mitchell and Billy Cox, the trailblazing rhythm section that laid the foundation beneath legendary rock guitar genius Jimi Hendrix during the last 16 months of his incendiary career.

Mitchell is without question one of rock’s greatest drummers, his unique, propulsive virtuoso style exemplified on masterful Jimi Hendrix Experience tracks like Hey Joe, Manic Depression, Purple Haze, Spanish Castle Magic, and 1983…(A Merman I Should Turn to Be).

Billy Cox, best known for his bass work with Jimi in the Band of Gypsys, was one of Jimi’s first musical comrades: the two met while stationed in the army at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in November 1961, and they immediately struck up a strong, lifelong musical relationship.

“We found that we had a lot in common,” Cox says of meeting Hendrix, then a 19-year-old guitarist. “Right away, I heard something in his guitar playing that captivated me. I knew this was a guy I wanted to hook up with.” They immediately formed a band and, one month later, moved in together in Clarksville, Tennessee.

By 1963, Hendrix had hit the road as a backup guitarist for the likes of Little Richard, Ike and Tina Turner, and the Isley Brothers. When his big break came in 1966 via producer/Animals bassist Chas Chandler’s invitation to go to Europe and form his own band, Hendrix reached out to Cox, who was unable to make the commitment. Within a month, Hendrix had signed on Noel Redding as bassist and Mitchell as his number-one drummer.

As fate would have it, Cox and Mitchell did eventually get to play together behind Hendrix, making their debut as a rhythm section at the legendary Woodstock Music and Arts Festival, on August 18, 1969.

While the festival has taken on mythic proportions over the years, Hendrix’s performance at Woodstock has never been accorded the attention given to much of his recorded output. That situation has been rectified with the new two-disc DVD, Jimi Hendrix: Live at Woodstock Special Edition, which restores the guitarist’s performance with loving care.

All of the existing footage of Hendrix at Woodstock is presented uninterrupted, re-edited and in its original performance sequence. The set gives fans a chance to view previously unavailable performances of Foxey Lady, Message to Love, Hey Joe, Spanish Castle Magic and Lover Man. Best of all, the soundtrack includes 5.1 and 2.0 soundtracks mixed by Eddie Kramer, Hendrix’s original engineer.

Among the numerous DVD extras are new interviews with Woodstock promoter Michael Lang, Mitchell, Cox, and Hendrix band members Larry Lee and Juma Sultan; privately shot and never-before-seen black-and-white video of much of the guitarist’s Woodstock performance; a Hendrix press conference filmed at Frank’s Restaurant in Harlem on September 3, 1969, two weeks after Woodstock; and Eddie Kramer’s recollections of recording the entire festival.

Although Mitchell and Cox fell out of contact after Hendrix’s death, they hooked up again in recent years. Today, the camaraderie between them is undeniable.

“Billy and I reconnected about four or five years ago,” says Mitchell, “and I am so grateful. We have such a nice comfort zone together, both personally and on a musical level. We push each other in a really nice way, and that’s what I think musicians need from each other. That’s what we are here for. I am lucky to have such a good friend as Bill.”

Your first gig together was at the mother of all rock festivals, Woodstock, in 1969. Bill, when did you first hear from Jimi about joining back up with him?

Cox: “We had hooked up in Memphis, Tennessee, in April of ’69, and Jimi told me he wanted me to come up to New York to be his bass player for some recording sessions. So a few weeks later, I flew to New York and we immediately began working on new songs together.

“He was overdue for another album at the time; the latest thing that had come out was Smash Hits, a greatest-hits package. Jimi didn’t have much new music prepared, so there was a lot of work to do. Jimi and myself – sometimes along with [drummer] Buddy Miles and sometimes with Mitch – sat down and began putting new, fresh rhythmic patterns and riff ideas together in order to create some new songs.”

You and Jimi spent a lot of time jamming and performing together while in the army and afterward, when you lived together in Tennessee in 1962 and 1963. Did any of these song ideas date back to those days?

Cox: “Actually, some of these things did date back to our earlier days together. We revisited these things and added new ideas to them. Our routine became this: I’d go over to his apartment in the morning, we’d practice for half the day, eat some lunch, and then practice and write for the entire rest of the day.”

Were the two of you working creatively from the start?

Cox: “Definitely. We always had fun when we played together. Playing music was the thing both of us liked doing more than anything else. We didn’t play golf, we didn’t bowl, we didn’t go fishing – we played music. It was our hobby, but it was also our profession. We loved doing it. The more time we spent together, the more in sync we got, and all of the new songs started to come together.”

Even though you were writing with Jimi in his hotel room and recording in the studio, Noel Redding was still the bassist for the live shows, correct?

Cox: “Right. I wasn’t officially in the group yet. Jimi was fulfilling his commitments with the original Jimi Hendrix Experience at that time. I was helping Jimi get his head together and find his new direction.”

Mitch Mitchell: “It was a strange time, a bit of a weird transition period, really. Actual fact, Noel was trying to get his band Fat Mattress together – which Jimi liked to refer to as Thin Pillow! – so they could open shows for the Jimi Hendrix Experience. It was a bit of a con game: he was trying to get paid twice for the same gig, playing guitar with his own band and then playing bass with ours. This used to really peeve off Jimi.”

It’s been well-reported that there was a lot of tension in the Experience between Jimi and Noel. Jimi was starting to use other musicians – bass players among them – and had also recorded many of the bass parts on the JHE recordings himself. Plus, Noel wanted to write more for the group.

Mitchell: “There was a variety of issues. If Jimi and I presented anything in, say, a Motown style to Noel, he’d react negatively. At the time, the only music Noel listened to was two albums by the Small Faces. The Small Faces were great, but that’s not where our heads were at.

“Noel had no knowledge of [legendary R&B/soul bassist] James Jamerson or the guys that played with James Brown. The bigger problem was that he had no interest, either. Billy, on the other hand, was a bassist; he had put the work in on the instrument. Noel, God rest his soul, had no interest in the bass as an instrument.”

In the early part of ’69, it seemed that things were good within the original Experience trio: the January performance on It’s Lulu [a U.K. TV variety show] was excellent, and the Royal Albert Hall show on February 24, 1969, is considered by some to be the best show the Experience ever played.

Mitchell: “The Lulu show was fun. If you are asking my opinion, though, the second Albert Hall show was adequate, and the first show [on February 18] was absolute crap! You see, there were management things going on that drove us crazy. [Hendrix’s manager] Mike Jeffery had put together a package show with us, the Soft Machine, the Eire Apparent and a few other bands, depending on the venue, plus this film crew led by Jerry Goldstein and Steve Gold.

“These film guys were costing us an arm and a leg; they were in our way, and they were incompetent in that they couldn’t record or film anything adequately. Consequently, the first Albert Hall show was a disaster.

“With the Experience, we had done a festival show at Devonshire Downs [on June 20, 1969] and we played like shit, frankly. We were getting paid a lot of money for this gig, and we had become so wrapped up in our financial situation that all we could think of was the amount of money we were making per minute.

“Jimi was so disgusted that he had the balls to go back two days later and play with Buddy Miles for free, to try to save face. In a way, the second Albert Hall show was similar in that we knew we had to make amends for the first show.”

Mitch, in the spring of ’69, had Jimi spoken to you about bringing in Billy Cox as the new bass player?

Mitchell: “Jimi and I had spoken about replacing Noel a few times over a couple of years, because there was always a lot of frustration there. I’m sure he had told me about Billy, and when we finally did play together for the very first time, we probably just nodded at each other and got right to it!”

Cox: “That’s right! [laughs] We just jumped in together, and with the three of us, it sounded good to me right away.”

Mitchell: “I have some film of those early sessions, in fact. I can’t speak for Jimi, but Billy’s presence on the bass immediately took a lot of weight off of me, which I greatly appreciated! I was now playing with a real bass player, and it was great.”

Billy, when you first came to New York, didn’t you do some gigs as the bassist for the Buddy Miles Express, which Jimi was producing at the time?

Cox: “Right. While Jimi was finishing up his commitments with the original Experience, Buddy told me he liked my playing and asked me to join his band. I had to learn his whole album within a week – I slept with it! – and then I did a handful of gigs with him ’till Jimi was ready for me.”

Mitchell: “Jimi and I had different musical tastes – he turned me on to Dylan lyrics and I used to play him John Coltrane and Roland Kirk – but we did see eye to eye in the bass player department. Noel, bless his heart, went to see Bob Dylan once at a gig in Ireland, and Bob told Noel that he liked his bass playing on Jimi’s recording of Bob’s All Along the Watchtower, which, of course, is really Jimi on bass.

“It was just so much easier to make records with just Jimi and myself, because Jimi was one hell of a bass player. In actual fact, he played better bass when he played a right-handed bass upside down!”

When Jimi played bass during a session, did it change your approach to the drums?

Mitchell: “Most definitely. Jimi was so solid, I could actually play less and leave more space; those were some of the only times when I wasn’t compelled to overplay, at least until Billy came onto the scene. Jimi and I were always aware that we needed a funky, rock-solid bass player. I had some fantasies about really fattening up the bottom end, by getting Larry Young on organ, maybe Howard Johnson on tuba, along with a killer bassist. I wanted overkill, miles of low end!

“I was once doing an album in New York and was asked who I’d like as a bassist on the session, so, being a bit of a wise guy, I said Chuck Rainey on electric bass and Richard Davis on standup. The next day, they were there! Richard had his lion-headed acoustic bass, and Chuck had his convertible Ampeg B- 15 amp and Fender Jazz Bass, and he parked himself right next to me. It was wonderful.”

While working on his previous studio effort, Electric Ladyland, Jimi had expressed in the press a strong desire to work with different musicians in the pursuit of new musical forms.

Mitchell: “That’s true. Jimi and I had both become very disillusioned with the situation with the band. It was becoming increasingly difficult to break new ground. We encouraged each other to play with as many different people as possible, and there were a handful of people who had played with us in the studio and live, such as Buddy Miles, Steve Winwood, and Jack Casady.

“The studio was where Jimi lived; in truth, if he could have lived in the studio 24 hours a day, he would have. The studio was a natural instrument for Jimi, one with which he possessed an uncanny ability to express himself.”

Billy, I’ve got to ask you something: did you ever work with Buddy on any studio dates other than with Jimi?

Cox: “No, I only worked in the studio with Buddy and Jimi together, never just Buddy. There have always been rumors to that effect, but the answer is no.”

Mitchell: “I once asked Buddy to come and sit in with Jimi and Noel at Winterland in ’68 just because I wanted to hear what the band [would] sound like!” [laughs]

Billy, immediately after you arrived in New York, you and Jimi recorded a number of times at the Record Plant, right from the start forging arrangements of new compositions like Earth Blues, Message to Love and Straight Ahead, as well as the complex masterpiece Power of Soul. How did that song come together?

Cox: “I was playing an old Ray Charles song called Mary Ann, which has some similar bass patterns, and Jimi heard it, picked up on it and then wrote new riffs for it. All of those new songs, like Dolly Dagger, came together during that spring and summer.

“With Dolly, we were up at the house in Woodstock [actually Shokan, New York], and one morning I started to play a riff that sounded like Big Ben, [sings] ‘Dada- da-da, Da-da-da-da,’ and Jimi added a twist to try to top me. Then I’d play another line to try to top his, and of course he’d end up topping me every time! So that’s how we worked together, and it was always fun and with a good musical spirit.”

Mitchell: “I noticed from the get-go that there was genuine warmth between Billy and Jimi. I didn’t know anything about their relationship beforehand from their army days; I just knew that they went back to the chitlin’ circuit together. But they would spend a lot of time together, working on music as partners; this was the first time in my three years with Jimi that he’d ever had anyone to work with like this and bounce ideas off.

“In Billy, I also saw someone that was prepared to play on Jimi’s level, and had real enthusiasm about the work and was willing to sit for hours and hours getting things together. This was right from the start, way before the Band of Gypsys [Hendrix’s subsequent three-piece group with Billy and drummer Buddy Miles].

“There was a synchronicity; there was contact. For me to see my friend Jimi getting his socks off being able to play off someone else was really great; he’d never had that before, for as long as I’d known him. I saw it and I felt it.”

So Jimi’s daily routine changed dramatically?

Mitchell: “Oh, definitely. I’d leave Jimi’s 12th Street apartment and he and Billy would stay there and continue working on music for hours, however long it took them to get the new ideas together. The feeling was so great.”

Cox: “Then we’d put these ideas down on tape – we always had our little tape recorders running. After rehearsal, we’d get some sandwiches, listen back to the tape, and then I’d go back to where I was staying, listen to the tape some more, and I’d think, Oh, I’m gonna improve on this tomorrow, and Jimi would be thinking the same thing. Then we’d come back together with more ideas the next morning. He’d say, ‘Listen to this!’ and I’d say, ‘Oh yeah? Well, listen to this!'” [laughs]

While the original Experience were playing live shows throughout May 1969, Jimi returned to New York on a half dozen occasions to record new songs in the studio with Billy and a variety of other musicians. The spring tour culminated on June 29 at the Denver Pop Festival, after which Noel Redding left the band.

In July, Jimi moved to Shokan in upstate New York to prepare for the upcoming Woodstock show on August 18, ultimately settling on a lineup of Larry Lee on guitar, Billy on bass, Jerry Velez and Juma Sultan on percussion and Mitch on drums, and called the new ensemble Gypsy Sun and Rainbows. What are your recollections of that time?

Mitchell: “The first thing is, we didn’t know that we’d come to the end of the Experience. It was never defined. Billy and I had done a bit of playing in the studio together, and it was always good. But regarding Noel, there was nothing definitive one way or the other. There was this ‘floating’ situation, wherein Noel was concentrating on Fat Mattress, I had gone back to England, and Jimi began working with some of the guys that ended up at Woodstock.

“I felt in my heart that Jimi and I would work together again and never gave it a thought, but nothing whatsoever was discussed.”

Cox: “It was a little awkward, because no definite plans were laid out. Jimi expressed to me that he was tired of the trio format and he wanted to make some changes. He tried an expanded lineup at Woodstock, but ultimately the bigger group didn’t work out. Personally, I like the trio concept best.”

Mitchell: “I got a call in July asking if I’d consider coming to New York to prepare for the Woodstock show. I’d lived up there before, at Mike Jeffery’s house, so I knew the area well and liked it very much. And I only got the call because something wasn’t happening up there, I suppose. [To Cox] Didn’t you guys have another drummer at one point?”

Cox: “Yes, we had played some with Phil Wilson, from the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, but that was really just jamming. I think Jimi knew he really wanted Mitch to be the drummer.”

Mitchell: “When I got to the house, it was a shambles! A ramshackle house – with some very nice people, like Claire [Moriece] the cook – but I had my doubts from the beginning. The world and his wife was up there. To see Jimi riding a horse was a sight to behold!” [laughs]

Cox: “I have a picture of Mitch falling off his horse!”

Mitchell: “I remember that Eric Barrett, the roadie, had an air rifle, and when he fired it he shattered the windscreen on Mike Jeffery’s jeep! It wasn’t intentional of course! It was craziness up there, for sure. I think I have a realistic view of this period and, for me, my memories of the Woodstock situation are that it was not brilliant, musically.

“It was fortunate that Billy and I had played together a little bit beforehand, because the percussion players, Jerry Velez and Juma Sultan, didn’t really cut it for me, no offense intended. I was very grateful that at least Billy and I had begun to forge a strong musical bond.”

Cox: “We had each other, and we knew where we were each coming from, musically speaking.”

Mitchell: “We knew where we sat together. I do think the other players were out of their element, because it is a difficult thing to be thrown into what had been, for Jimi and myself, a well-established working relationship, one that had lasted nearly three years at that point. These guys were thrust into the limelight, and I think they were in awe to a certain degree.”

Though the band sounds rough-hewn at times, there are certainly many brilliant moments during the Woodstock performance.

Mitchell: “What most people don’t realize is that the sound equipment in those days was sorely lacking, especially when it came to monitors. I had nothing, so I had to rely on watching people’s hands. You couldn’t hear what you were doing, so it made it very tricky. As an ensemble, the Woodstock band, to me, left something to be desired.”

One of the highlights of the Woodstock show was the great new material that was showcased, such as Izabella, Message to Love, Jam Back at the House [later retitled Beginnings] and Villanova Junction.

Cox: “Villanova Junction [the slow A minor blues that culminates the Woodstock performance] was just a simple blues Jimi devised up at the house. That repeated melodic riff is really just a takeoff on a typical Curtis Mayfield type of melody, without really being based on any particular tune. It’s the Curtis flavor.”

Mitchell: “Jimi ‘stole’ from everywhere; if it was out there, he’d take it and twist it into something else.”

Cox: “We hung out up at the house for about three weeks, and played a lot, though the rehearsals were extremely informal. It was a wild scene up there, between trying to keep the groupies and other characters away. In truth, we all worked on music constantly, in spite of the ‘interruptions’ and the general madness. The downstairs living room was the main practice room, with all of our big amps and equipment, and upstairs was another practice room.”

Bill, another cool thing was that you devised great new bass lines for many of the older Experience songs, such as Fire and Spanish Castle Magic. You played these songs in your own unique way.

Cox: “I gave them another flavor. Jimi encouraged me to add things in the gaps. He’d say, ‘What would you do there? Would you play a line going down? Going up? Add a different run?’ Jimi had some specific things in mind for the bass parts; that’s why he played the bass himself on so many of the studio recordings with the original Experience.”

Mitchell: “Noel didn’t like it at all when Jimi told him what bass line to play. With Bill, there was always enthusiasm for any idea Jimi wanted to pursue. Bill would quickly grasp the structure of the tune, and then he’d add his own personality, which was great.”

The Gypsy Sun and Rainbows band was unique in that it was the only time Jimi ever utilized a second guitarist. What was Jimi’s history with guitarist Larry Lee?

Cox: “Jimi knew Larry from our post-army days together in Tennessee. At the time, Larry had helped Jimi out quite a bit, guitar playing-wise, and Jimi respected Larry as a player. They were good companions. When we were first putting this group together, Jimi said to me, ‘I’ve got to find Larry Lee!’ So I did, and Larry showed up a few days later.”

Mitchell: [To Cox] “Bill, do you think Larry ever felt really comfortable working in that situation with us?”

Cox: “No, I don’t. He came to me many times and said, ‘Look, Jimi is playing so much guitar; what is there for me to play?’ Larry was a great player, and he had his important place in Jimi’s earlier history. But by 1969, Jimi had evolved so much. They’d throw licks back and forth at each other, and a lot of it sounded good, but Larry felt that Jimi had come so far, and his own playing was not that effective.

“The truth is that any other guitar player would have sounded inadequate onstage next to Jimi. I said to Larry, ‘Let’s do this gig, have a good time and take it from there.'”

Jimi was certainly encouraging of Larry in that he gave him many solos; they play some tandem/trade-off licks together; and the band also performed one of Larry’s compositions, Mastermind, at Woodstock.

Cox: “Jimi was very encouraging of Larry in that I think he did like Larry’s playing and he liked playing with him. Larry had also brought the Curtis Mayfield tune Gypsy Woman to the table, and when we played that song at Woodstock, Larry sang it and Jimi sang backup. In fact, Jimi, Larry and myself toured as the backup band for Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions back in the early Sixties for about a dozen gigs within a 150-mile radius of Nashville.”

Mitchell: “Jimi was the first person I ever met who could play all of those incredible Curtis Mayfield rhythm parts right off the top of his head. He knew that stuff backward and forward. Jimi retained so many different bits of knowledge, all across the board and in every style. I could see that Jimi really respected Larry, and that Larry was a great player, but, unfortunately, I never really got the chance to know him.”

Cox: “There was so much happening then; it was really a crazy time. From my perspective, from the short time we had to get new things together with a new group of people, Woodstock was an incredible show, one that many people enjoyed, and still enjoy hearing today.”

Mitchell: “I know it’s not a ‘romantic’ viewpoint, but I can’t help but think of the logistics of the Woodstock event, which were trying. The first major show I ever played with Jimi was the Monterey Festival [on June 18, 1967], and it was so much better organized than Woodstock.

“At Woodstock, we were supposed to fly in by helicopter, but because there was mud everywhere, Mike Jeffery had these ex-CIA guys drive us in a couple of rickety old station wagons, which took about five hours just because of the traffic and the mass of people. We were due to go onstage at midnight to 1 a.m., as we were the headliners of the three-day event. When we eventually arrived at the site, we asked, ‘Where is the dressing room?’ We were told there were no dressing rooms, and they pointed to a cottage across a rotted, muddy field about a half a mile away.

“We went over there, tried to keep warm – my wife was pregnant, too – and then we had to wait about eight hours before we played. It was like an army maneuver! [laughs] Absolutely foul! I was also witness to a variety of, shall we say, security breaches… Things were pretty out of hand, to say the least.

“I guess I do give a monkey’s fart about the whole thing, but only if the music can hold up over the years. Back then, we never could have guessed that, all these years later, people would be listening to it and enjoying it for the very first time. I never sit and listen back to the stuff. In the Monterey film, for instance, I can see that we went out there and kicked some backsides.”

Cox: “From my perspective, the Woodstock festival was history being made right before our eyes. So many people had converged on that one area, right at that moment. It was incredible. Woodstock was the mother of all of the rock festivals that followed.”

In retrospect, Jimi’s performance of the Star Spangled Banner that day is regarded as the shining moment of the Sixties youth movement; in those electrifying three minutes, he was able to capture the power, the beauty, and the vibrancy that the Sixties counterculture has come to represent.

Cox: “That was completely impromptu. I know Jimi had played it before on a few shows, but we hadn’t played it or discussed it. If you listen to the recording carefully, you will hear me start playing along with him; I was glued into where he was at – his posture, and where he was going mentally and physically. When he started playing the Star Spangled Banner, I started to play with him, but I got the feeling I should lay out, so that’s what I did.

“I let him continue, which I think was the right thing to do. That was history – he wanted to make a statement, and what an incredible statement it was. Some people have tried to interpret Jimi’s version of the song as something negative, but it was really just a beautiful artistic statement. An electric guitar never sounded like that before! And there was no negative connotation; let’s not forget that Jimi had done his time in the army, the 101st Airborne Division.

“We fulfilled our obligation to our country and ourselves, and we left the army with pride. Jimi didn’t burn his draft card, as some young people were doing at the time. He thought that was a deplorable thing to do. He played the Star Spangled Banner from his heart. He loved this country; it was something we had talked about a lot.”

Machine Gun was another way Jimi expressed his feelings about the country at that time.

Cox: “War is nothing to be proud of. There will be wars as long as there are human beings, and it is very unfortunate that blood is shed. But it is a prophecy.”

Mitchell: “I am aware of and can appreciate the historical significance of that moment in retrospect. But in real terms, it was 9:00 in the morning; a lot of people had left because we were due to be on hours before; we were very tired, it was very cold and we couldn’t hear ourselves. There’s nothing worse than people saying to you, ‘Hey man, great show!’ when you know that it wasn’t. You know when you have played well, and that kind of thing would really bother Jimi a lot.

“I cannot romanticize Woodstock; I won’t do it! If we went on earlier it would have been better, because, at the very least, the audience was completely drained by the time we did go on.”

One of the tunes showcased at Woodstock, Jam Back at the House, was later retitled Beginnings and credited to Mitch Mitchell, and features incredible polyrhythmic drum syncopations.

Mitchell: “That was my tune, and thank you. It was really built from drum patterns I’d ‘stolen’ from listening to Art Blakey and Elvin Jones and is based on African rhythms. This is something that was so wonderful, so pleasing, about working with Jimi, because he was so open to any musical suggestions and things came to him so naturally.”

Following the Woodstock festival, the Gypsy Sun and Rainbows band made a few studio recordings in September but soon broke up.

Mitchell: “I think I can speak for Jimi when I say that, ultimately, he was not happy with that lineup and he knew things had to be changed once again.”

Cox: “The management were always giving us hell because we spent so much time writing and recording in the studio. Of course, here we are 35 years later and everyone praises us for the work we did!”

Mitchell: “That was why Jimi ended up putting his ass into so much debt with the building of the Electric Lady Studios. Owning his own studio was something Jimi wanted, and very much indeed.”

It’s been intimated that Jimi’s management took an active role in disbanding this ensemble.

Cox: “The truth is that there was a lot of tension in the air, in that the management was trying to pressure Jimi into changing things without regard for what Jimi really wanted to do. These gun-carrying heavies would show up at the house with Mike Jeffery, and things were a little scary.

“They wanted Jimi to put a different band together and go back out on tour immediately – they tried to force him to audition different players – but Jimi knew what he did and didn’t want to do.

“Ultimately, there was no tour, so following the few commitments we had after Woodstock, I went back to Nashville and Mitch went back to England. But I was back in New York about a month later, because part of what was going on involved what at that point had become a long-standing and unresolved legal issue with Ed Chalpin [Hendrix had signed a recording contract with Chalpin back in 1966].

“Ultimately, the decision was made to give Chalpin an album as part of the settlement, which turned out to be Band of Gypsys [recorded by Hendrix, Cox and Buddy Miles under the name Band of Gypsys].”

Mitchell: “Jimi and I had always had a correspondence, even during the Band of Gypsys period [from November ’69 through the end of January ’70]. At the time, I worked in a group with Jack Bruce and Larry Coryell, and Jimi came to see our gigs at the Fillmore.

“I was still staying at Jimi’s 12th Street apartment! And even during the Band of Gypsys period, Jimi called me and expressed some personality conflicts within the group, which had nothing to do with Billy I hasten to add. My feeling is that, if Jimi were alive today, we would probably not have a regular band together, but I’m sure we would have always gotten back together for recording and to play shows.

“We did work with a few other lineups – horn players or what have you – so we got to explore that a little. Regrettably, we never got to further explore larger ensembles and different instrumentation with Billy.”

After the fallout from the Band of Gypsys, Jimi’s management decided that it’d be best to get the original Experience back together, right?

Mitchell: “Yes. Jimi, Noel and I did an interview with Rolling Stone wherein we’d announced the reformation of the original lineup, but things didn’t feel quite right. Jimi called me at about 10 o’clock that same night, and he said, ‘So, how do you feel about it?’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ and he said, ‘About Noel.’

“I didn’t say anything – I suppose I was waiting for someone else to say something! He said, ‘Well, we’ve played with Billy…don’t you think it’s time [to let Noel go]…’ and I said, ‘Yes!’ There was a certain amount of resentment from Noel’s side, bless his cotton socks. He was an adequate guitarist, and the bass was never his instrument. He played very proficiently, but he didn’t care for the instrument at all. He didn’t try to learn about the bass, and that used to bug the shit out of Jimi and myself.

“Noel, and Chas [Chandler] as well, weren’t interested in experimenting in the studio, either; it was all about getting it done quickly. Chas would always say, ‘The House of the Rising Sun [the Animals hit song on which Chas was the bassist] cost $30 to record,’ but, truthfully, that was meaningless to me and Jimi. That was then; things were changing.

“We liked to work hard in the studio; we lived for it. I had worked in the studio quite a bit before I had ever even met Jimi, and I’d never seen anyone work so naturally in the studio as him. To Jimi, the studio was just another instrument. The closest person to Jimi in that regard was [legendary Atlantic Records producer/engineer] Tommy Dowd, who is generally and rightfully regarded as a genius.”

One of the great things about a truly effective power trio lineup is that the three musicians learn how to make a huge, powerful sound with just one guitarist, a bass player and a drummer. The personality of each individual has to be very strong in order for the trio lineup to really work. This was true of Eric Clapton, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker in Cream, and it was certainly true in the original Experience and also in Jimi’s later trio with you both.

Cox: “In a trio, each musician must carry a lot of weight. We three, as a band, knew how to do that, and we loved doing it. We enjoyed great communication with each other, visually and musically.”

Mitchell: “That’s the deal. I have always attempted to learn what not to play and to leave the proper amount of space for the other musicians. And I do believe that the three of us did have great musical and personal communication.”

Did the experience of playing together at Woodstock fuel the desire to shift back to the trio format?

Mitchell: “It was something that was never said, but it didn’t need to be said. In February of ’70, after Jimi and I decided we wanted to play with Billy instead of Noel, a few other musicians were discussed as possible fourth additions, but the primary focus was to go back to the trio format.

“The Band of Gypsys was something Jimi wanted to see through to fruition; it was brilliant, he did it, enjoyed it, and then it was time to move on. I had just moved into a wonderful giant house in England with loads of expenses and I waited to see what would happen next. Jimi, Billy and I rehearsed in Los Angeles in the spring and immediately started the next tour.”

After all Jimi had been through in the previous year, and all of the managerial hassles, what was the feeling in the trio like at that time?

Cox: “It was great. Jimi knew where we wanted to go, and we knew how we were going to get there. We had some great shows, and a lot of fun onstage, and the studio material speaks for itself.”

Mitchell: “From my side, I was much more comfortable playing-wise than I had been for a long time. Billy provided a great anchor, a solid bottom end, and he didn’t use a plectrum! I hate the sound of the electric bass played with a plectrum!

“Billy’s presence insured a much steadier and more reliable band sound, which made everything easier, and we were tighter. My only regret was that, before what turned out to be our last tour, we went about four weeks without playing, and some of those shows are not as together as I would have liked.”

One of the highlights, musically, of the spring tour was the composition, Hey Baby (The Land of the New Rising Sun). How did this masterpiece come together?

Cox: “In creating that song, Jimi and I starting talking about our connections with classical music. My mother played classical music on the piano, and I developed a love for Beethoven, Bach and Chopin.

“Jimi had a love for this music too. If you listen to the way Hey Baby develops, it is like progressive movements in a classical piece. We had planned to further develop that song and to write more music along those lines. If we had another 10 years, there’s no telling where our music would have gone.”

Mitchell: “The truth is, I don’t think Jimi, Billy and I, as a band, ever got to see what we could really do in the studio, because, unfortunately, Jimi passed away. Right after Jimi’s death, I attempted to put The Cry of Love together with Eddie Kramer, and that was really difficult and disconcerting.

“I just wish we three had had the chance to really play and record together in Electric Lady Studios much more than we had, in pursuit of what the vision for the future was.”

Do you two have any plans to play together again in the near future?

Mitchell: “I would really love to play more with Billy, especially if we look back at our material with Jimi and create some interesting new arrangements. Billy’s got it right when he says that we have a license to play this music, and I am excited about the prospect of our future collaborations.

“I’m lucky in that I am able to pick up a pair of drumsticks and play, and working with Billy is like sitting in your favorite comfortable couch.

“The word ‘tribute’ makes me uncomfortable, but I do love the music, and the idea of creating some new interpretations of the music we played together is enticing. It’s our music; no one can ever take it away from us. It’s a spiritual thing. I am so privileged to have been able to play with Jimi, and to have played with – and to continue to play with – Billy Cox.”

Cox: “I have always enjoyed playing with Mitch. We have been friends for over 35 years, and I think we’ll still be friends for a long time to come.”

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month*

Join now for unlimited access

US pricing $3.99 per month or $39.00 per year

UK pricing £2.99 per month or £29.00 per year

Europe pricing €3.49 per month or €34.00 per year

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Prices from £2.99/$3.99/€3.49