The “curious” creature with no anus was demonstrated to not be related to humans.

An international study team has found that a mysterious microscopic creature assumed to be the ancestor of humans actually belongs to a different family tree.

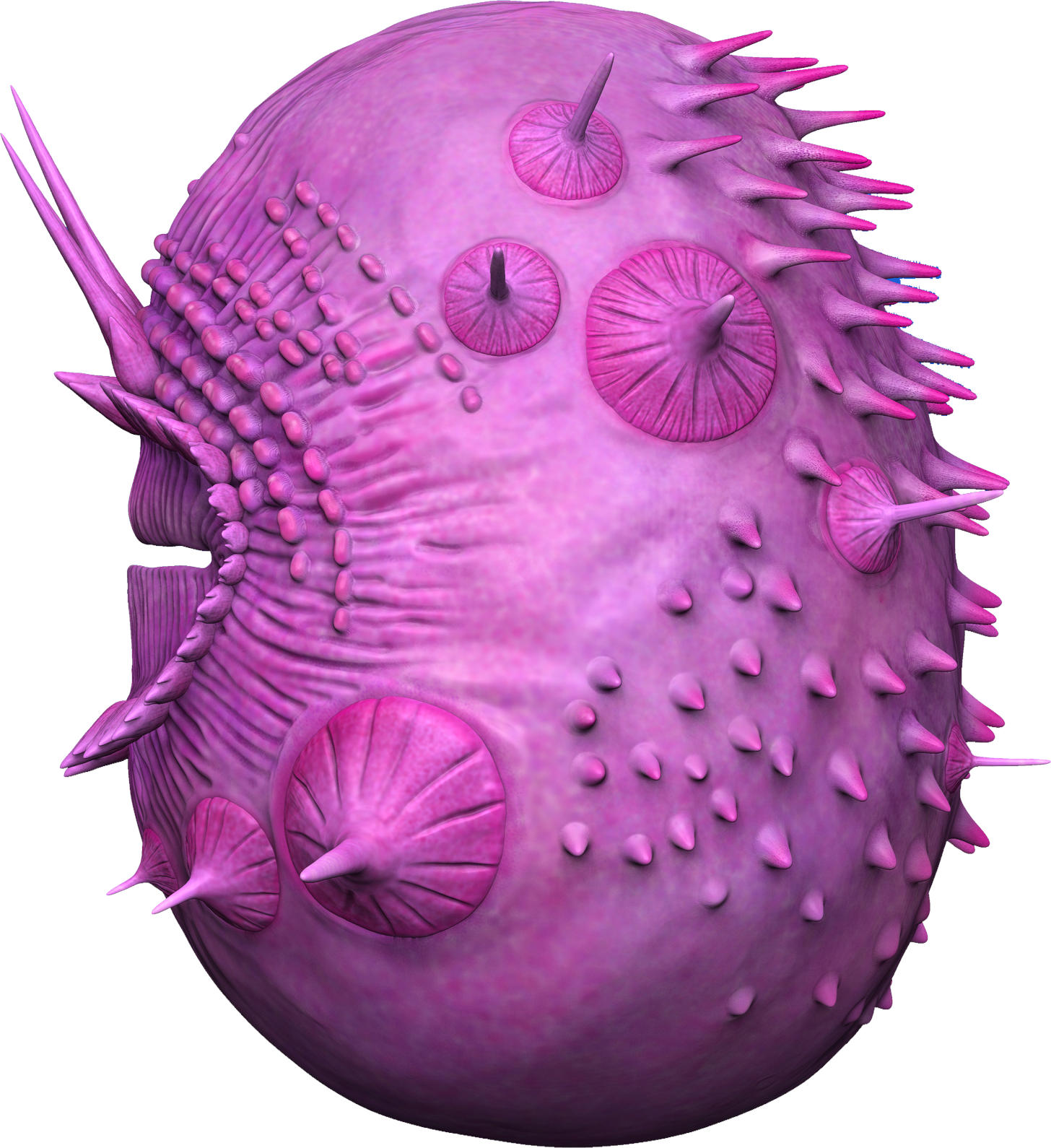

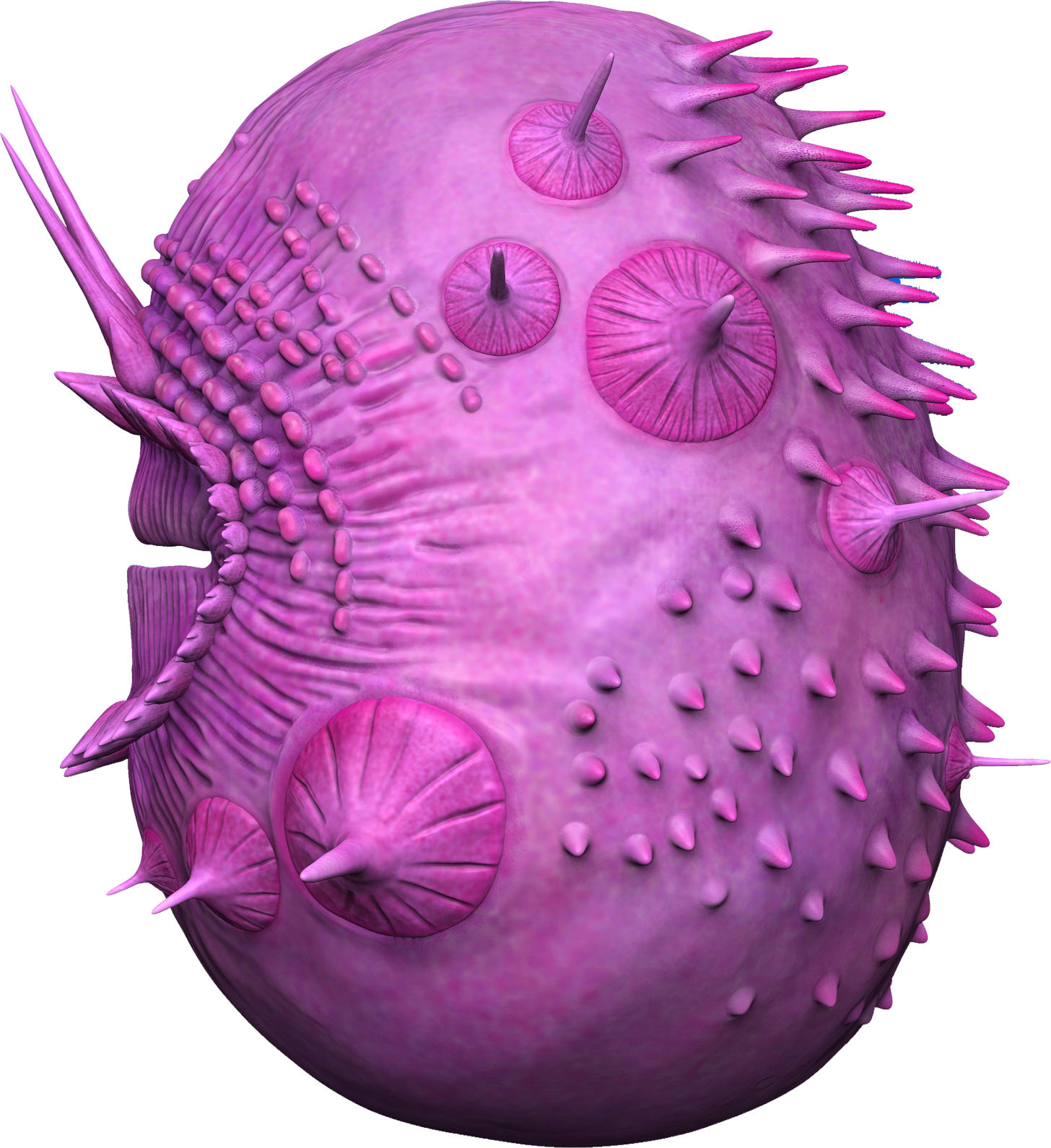

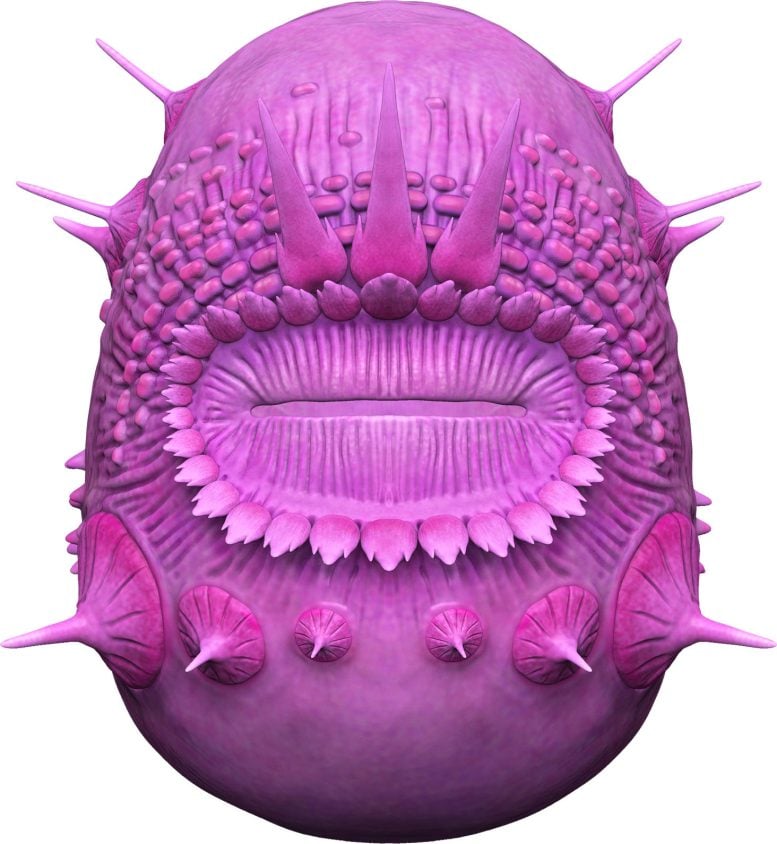

The Saccorhytus is a spikey, wrinkly sack with a huge mouth surrounded by spines and holes that were interpreted as pores for gills – a primitive feature of the deuterostome group, from which our own deep ancestors emerged.

But a thorough examination of fossils from China that date back 500 million years has shown that the holes surrounding the mouth are actually the bases of spines that split during the process of fossil preservation, finally revealing the evolutionary affinity of the microfossil Saccorhytus.

“Some of the fossils are so perfectly preserved that they look almost alive,” says Yunhuan Liu, professor in Palaeobiology at Chang’an University, Xi’an, China. “Saccorhytus was a curious beast, with a mouth but no anus, and rings of complex spines around its mouth.”

The findings, recently published in the journal Nature, make important amendments to the early phylogenetic tree and the understanding of how life developed.

The true story of Saccorhytus’ ancestry lies in the microscopic internal and external features of this tiny fossil. By taking hundreds of X-ray images at slightly different angles, with the help of powerful computers, a detailed 3D digital model of the fossil could be reconstructed.

Researcher Emily Carlisle from the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences explained: “Fossils can be quite difficult to interpret and Saccorhytus is no exception. We had to use a synchrotron, a type of particle accelerator, as the basis for our analysis of the fossils. The synchrotron provides very intense X-Rays that can be used to take detailed images of the fossils. We took hundreds of X-Ray images at slightly different angles and used a supercomputer to create a 3D digital model of the fossils, which reveals the tiny features of its internal and external structures.”

The digital models showed that pores around the mouth were closed by another body layer extending through, creating spines around the mouth. “We believe these would have helped Saccorhytus capture and process its prey,” suggests Huaqiao Zhang from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology.

The researchers believe that Saccorhytus is in fact an ecdysozoan: a group that contains arthropods and nematodes. “We considered lots of alternative groups that Saccorhytus might be related to, including the corals, anemones, and jellyfish which also have a mouth but no anus,” said Professor Philip Donoghue of the Virginia Tech, USA, who co-led the study. “We still don’t know the precise position of Saccorhytus within the tree of life but it may reflect the ancestral condition from which all members of this diverse group evolved.”

Reference: “Saccorhytus is an early ecdysozoan and not the earliest deuterostome” by Yunhuan Liu, Emily Carlisle, Huaqiao Zhang, Ben Yang, Michael Steiner, Tiequan Shao, Baichuan Duan, Federica Marone, Shuhai Xiao and Philip C. J. Donoghue, 17 August 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05107-z