Nobody would fault you for having a dodgy definition of a Luddite. In modern usage, the term is sometimes dropped in cocktail-party chatter, a fancy little thing that arrives wrapped in prosciutto and speared with a twirly toothpick. Ah, yes, he’s such a Ludditeone party passerby might say, plucking a Castelvetrano from a platter. Impossible to stay au courant with the intelligentsia when you’re like that. Maybe you’ve stood near enough artily-arranged plates of gruyère to get a better grasp. Right, rightLuddites: people who are stubborn about new technology, don’t care to adapt or engage, would rather reject our devices altogether.

You might be a Luddite, so it goes, if you scoff at screen time, or you’d rather not have Alexa listen in on your pillow talk. Perhaps you prefer cars be driven by people, not sensors and actuators, or that news be read from pages instead of push notifications. Maybe you arch an eyebrow at algorithms, wonder why machines should learn, would rebuff a chatbot who tries to say hello.

A certain kind of Luddism can be a mark of pride, like the city teens who trade iPhones for something approximating the analog. “When I got my flip phone, things instantly changed,” Lola Shub, a then-high school senior, told The New York Times about what she and her friends came to call the Luddite Club. “I started using my brain. It made me observe myself as a person. ”

To cast someone as a Luddite today is to do so with bemusement, to suggest they’re small-minded, a bit quaint, or fearful of technology. A Luddite cold-shoulders not only new tech, but of all the progress and potential it hastens forward.

That’s where journalist Brian Merchant would object. His new book, Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech,surfaces the forgotten story of the original Luddites—and why it should be recalled in a new machine age. These industrial-era clothworkers were perhaps the first people to watch machines come for their jobs. But rather than let the machines change their livelihoods, the workers staged a clandestine rebellion.

Amidst the age of artificial intelligence and automation, where Silicon Valley monopolies increasingly dictate the confines in which we live and work, it’s worth reexamining the story of the Luddites: the original anticipators of how technology can inflict harm, whose response may point the way through our new machine age.

The origins of the Luddites

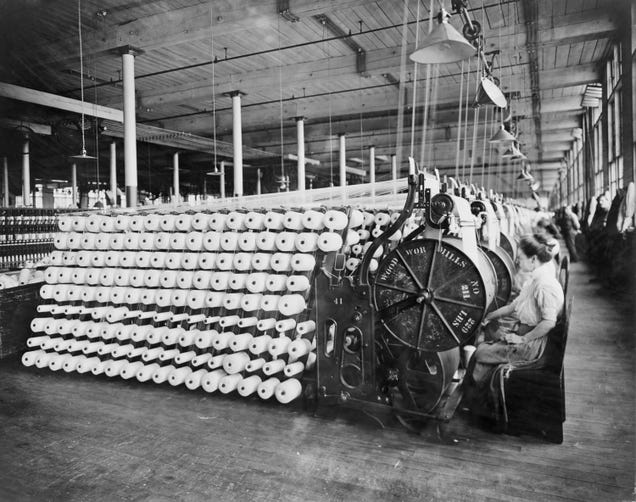

Textile work, as Merchant tells it, was the first corner of the modern labor market to be automated. In nineteenth-century rural England, weaving was a skilled, secure craft. Clothmakers worked in their homes, able to dictate their hours (generally about thirty a week) and their breaks (often); they earned middle-class wages and worked alongside their families. But by 1810, a new device would change everything—the power loom.

The steaming, spinning mechanism could perform the skilled work of weaving much more efficiently than human hands—and to the clothworkers’ alarm, wealthy factory owners began installing the machines in their communities. No longer could clothworkers weave in their homes among loved ones: if they wanted to stay employed, they’d get a job in a factory building, where they would operate dangerous devices, inhale flying fibers, and submit to a boss who determined when and where and how they worked. Wages went down. Children were hired. Class chasms widened.

A factory-running elite, the clothworkers recognized, would use the machines to undercut their craft—and enrich themselves in the process. But rather than submit, the workers took up arms. First, they issued anonymous letters to factory owners: Drop your machines, or you’ll meet Ned Ludd’s army. The makeshift militia was named for a fabled Robin Hood-type figure who begins as a factory boy who breaks his machine and flees triumphantly to the forest. When the power looms hummed on, the group made good on its word: they gathered in the night, broke into factories, and took hammers to the machines.

The Luddites began gathering headlines, with their machine-smashings chronicled in the local papers. The clothworkers would be joined by scores of working-class people, from shoemakers to coal miners, who were beginning to sense their exploitation at the hands of machine owners. Overnight fights would be staged on factory floors; blood would be spilled among the rich and poor.

The industrial age’s defining class struggle has been all but obliterated in modern memory, and perhaps worse, become oversimplified and mocked. In some ways, it’s no surprise that we’ve forgotten why the Luddites resisted the machines. We often have collective amnesia around the ways we’ve opposed the ascent of new technology; nobody, for one, seems to recall that half of sixties-era Americans were against sending a man to the moon. But as tech billionaires blast off into space on record profits and inequality widens for the Earth-bound left behind, we might remember the clear-eyed prescience of the Luddites.

Learning from the Luddites

Today, Merchant notes, we collectively subscribe to the idea that technology brings about progress and innovation. But the Luddites were the first to push back on the notion that technology was always a beacon of progress. That’s worth remembering as we enter a new machine age, one where intelligent technology is rapidly reshaping our work—and rousing fear about what it will mean for our own livelihoods.

Hollywood writers walk off the job so that future scripts won’t be constructed by chatbots, and actors strike so their likeness won’t be AI-engineered for the screen. Auto makers picket as robot arms cast shadows on the factory floor. Warehouse shippers and package drivers organize as digital systems dictate their delivery speed.

Across offices around the globe, employees begin to sense that they’re under surveillance, not by bosses, but by software. Workers are interviewing for jobs with computer-recruitersor pushed from full-time employment to gig work ruled by an algorithm. Reports project AI could shift millions of jobs by the end of the decade. We’re left wondering whether a machine will come for our career next.

This story of modern technology, as Merchant puts it, began not decades ago, but centuries. Working people sensed these new structures assembling; they spotted how tech-wielding titans would remake their social order. And as we examine how today’s machinations will shape our future, we might take up the cause of the Luddites: that everyone benefit from the gains of the machines.